Haskell Institute: The Roots from Which We Bloom 1884 – 1930

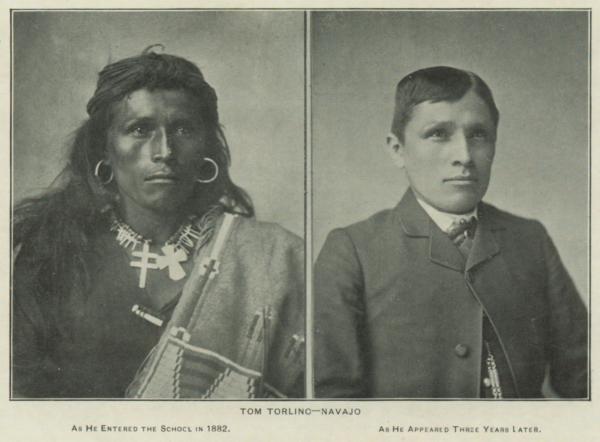

“Kill the Indian in Him, and Save the Man.”

In 1875 Richard Henry Pratt, an officer in the U.S. Military, had the desire to “educate” a group of Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Caddo, and Arapahoe prisoners of war in his possession, at the abandoned Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, also called the Castillo de San Marcos. By this one action, Pratt believed that he was saving thousands of Indians by training them with Christian and American-based school lessons, as Pratt would use the former fort as a schoolhouse. Pratt would create one of the most devastating tools in the process of genocide and the erasure of Indigenous peoples across the nation.

Pratt’s success in Florida sparked the creation of the first Indian Boarding School, Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1879. This one school inspired the creation of multiple schools just like it, with the ideology of a quote from Pratt, “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Imaged above is Tom Torlino, Diné student of Carlisle Indian School. This side by side shows the “exemplary” transformation of Indian pupils. The striving image of assimilation. Courtesy of Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

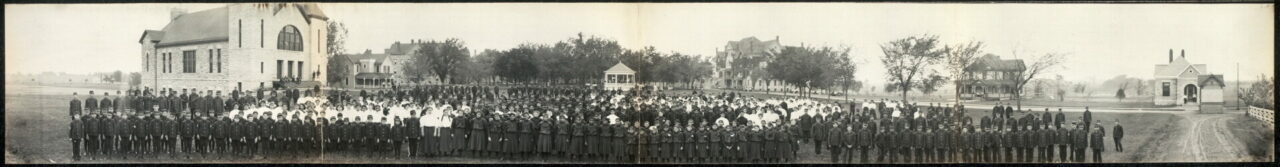

Cover photo: Participants in the October 1926 Haskell Institute celebration. Douglas County Historical Society archives.

Training School

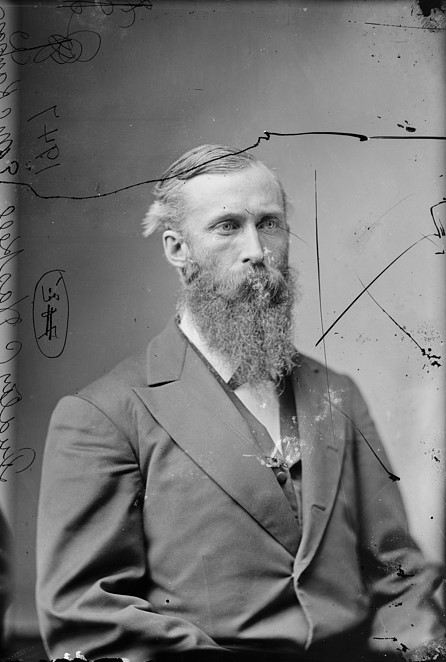

With the help of $10,000 from Lawrence locals, Dudley C. Haskell was able to create a school to begin the assimilation process of Indigenous children. Haskell was also a speaker in Kansas House of Representatives and worked within the U.S Congress. His actions in the creation of the Indian Training School were so impactful the school was renamed Haskell Institute soon after opening.

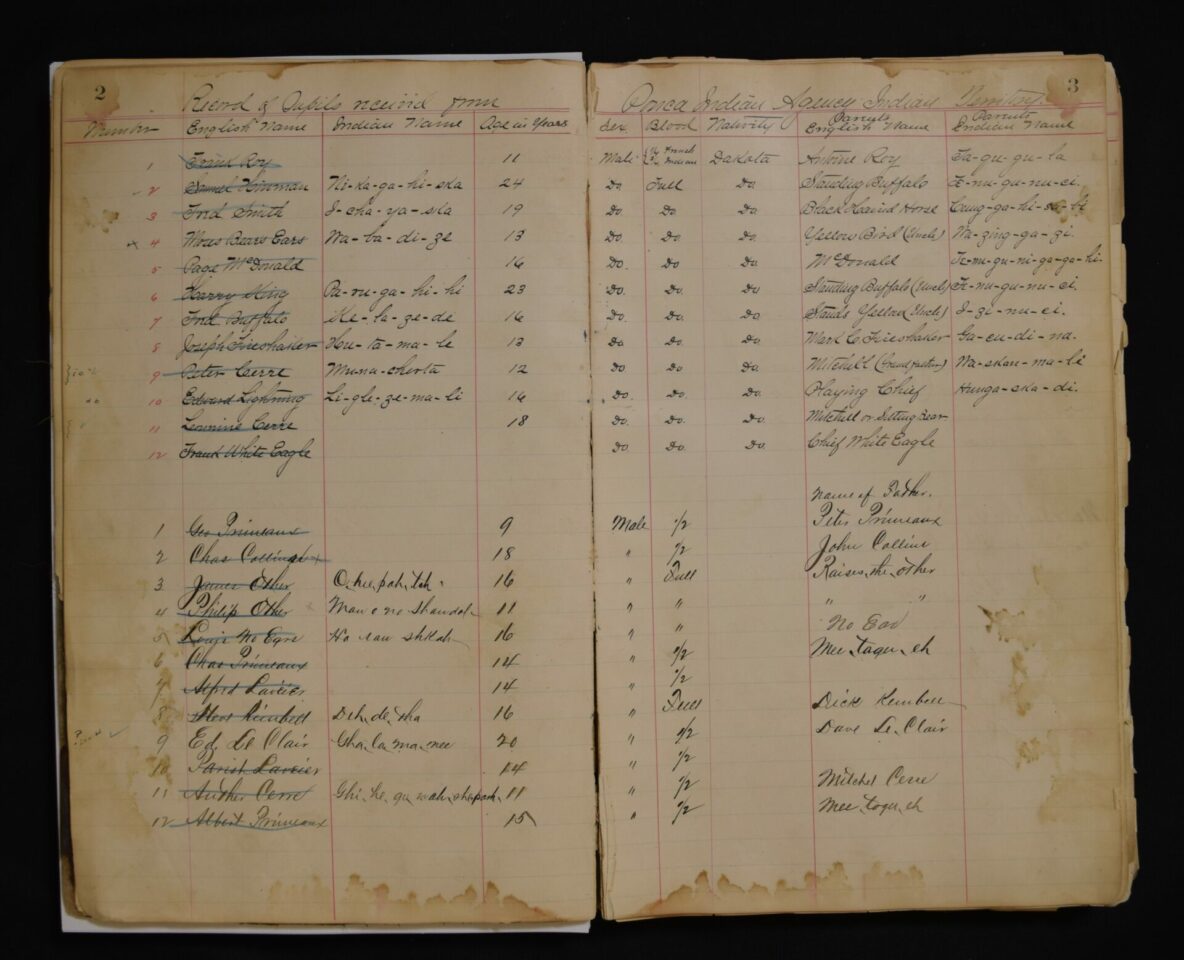

The United States Industrial Training School opened September 17, 1884, consisting of 22 children, ranging from age 11 to age 28. The children were from the Ponca, Ottawa, and Dakota Nations and transfers from Chilocco Indian School located in Indian Territory. These were the first students.

These 22 children not only constructed buildings on the property, but also the early development of discipline within Haskell Institute.

Imaged right is Dudley C. Haskell. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

A We vs I Mindset

These 22 children endured brainwashing and neglect, while simultaneously being told that their previous way of living was barbaric and savage. The children were being melted and molded into perfect American Christians. Before colonization, Indigenous people had had their own beliefs, religious figures, and creation stories, Indigenous people were sustainable and had their own ways of life.

A key tool in Indian Boarding Schools was the process of individualization. Many Tribes had a community-based life, living and working with relatives. There was no “I, me,” or “mine” it was “ours, us” and ‘we.” New Americans did not believe in this. American beliefs lay in the progression of a singular man and his accomplishments, not his brother or mother nor his children.

First ledger of the Indian Training School. Courtesy of Haskell Cultural Center.

Assimilation Process

There were four major changes when an Indian child arrived at Haskell Institute: hair cutting, clothes distribution, name changes, and influence of religion and white culture. In Haskell Institute, cutting hair was necessary for two reasons: first, for cleanliness and eliminating head lice, and second, for eradicating the image of the savage Indians, to transform them into average American citizens.

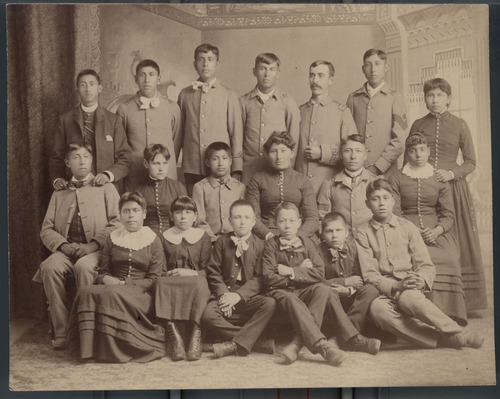

Imaged above, Haskell Institute students gathered for group photo in 1908. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Indigenous people’s traditional names can signify a prominent moment in a person’s life. For children this could have been reaching puberty, celebrating their first hunt, or a heroic action. Boarding schools would remove traditional names and replace them with names that were easier to remember and pronounce; this was a blatant attack on the children’s Indigenous identity.

Obliterating Indigenous Identity

The next step was the distribution of “new” clothes. When arriving at Haskell Institute, the majority of students arrived in their everyday traditional attire consisting of leggings or moccasins, handmade blankets, decorated shirts usually made of various animal hides, and jewelry like earrings and bracelets. By taking traditional clothes and replacing them with military-styled uniforms, Haskell was aiming to establish individuality within students when it just made them appear as soldiers.

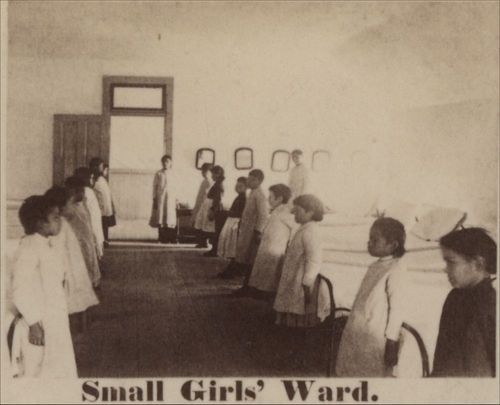

Above, Haskell Institute photograph of the Small Girl’s Ward, alongside a photo of a Shoshone child’s moccasins made of buckskin and decorated with beads. Left: Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply. Right: Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

Room and Board

Often, children would be locked into their rooms at bedtime and would not be allowed out until the morning. This encouraged the spread of disease due to being trapped in close spaces and also created issues concerning toilet usage. Staff would also track the girls’ monthly cycles. Boarding Schools also adopted the trend of “sleeping porches” where a few children, sick or healthy, would have their beds moved to the enclosed netted porches to sleep. The usage of sleep porches was also used to accommodate overcrowding in order to accept more students rather than accepting the limit of pupils.

Imaged above is a group of young children called the “Haskell Babies” dated 1880-1889. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

Flourishing Diseases

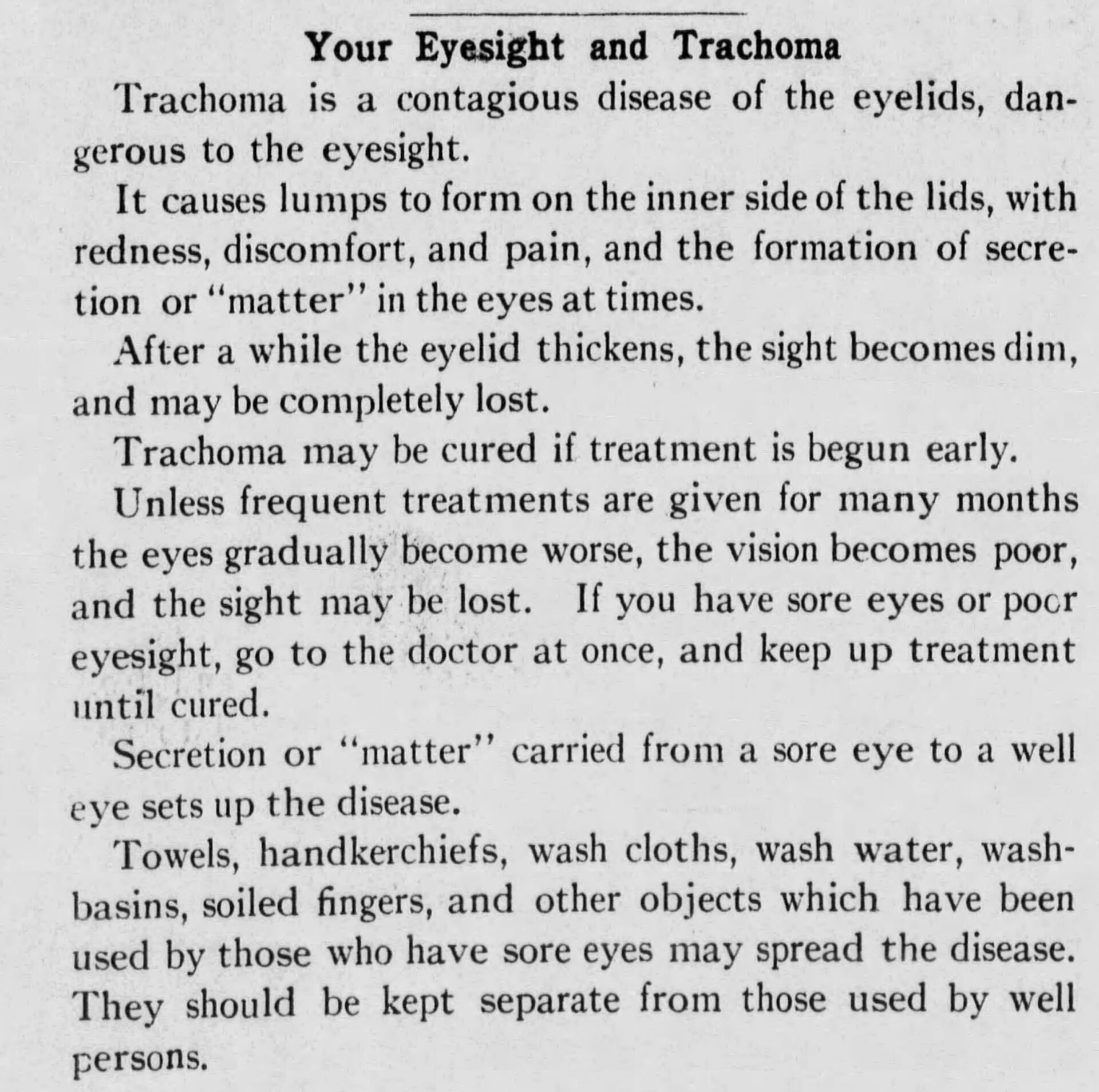

Disease would thrive within Haskell Institute, one of these diseases being Trachoma. This is a bacterium that causes vision loss and blindness, creating intense scarring on the inside of the eyelid and causing the eyelashes to scratch the cornea, leading to irreversible damage. Treatment that children received for Trachoma in 1937 was:

“Scraping or pinching the inflamed inner eyelid with small forceps, flushing the eye with a solution of boric acid, and lengthy follow-up treatments when the eyelid would be rubbed with a copper sulfate stick.“

Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons, 2012, pg. 59

Imaged above is a snippet from the Haskell Institute newsletter “The Indian Leader”, a piece from December 1924 concerning Trachoma.

Tuberculosis at Haskell Institute

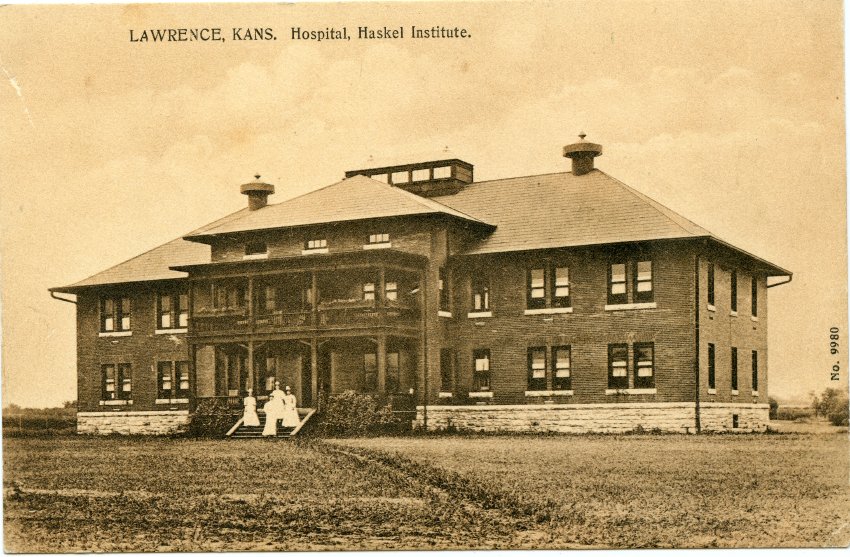

Another disease that affected Haskell Institute was Tuberculosis, or TB. Young children who were given such strenuous workloads and little sustainable foods, were impacted greatly. According to the CDC today, individuals most at risk for developing TB disease are young children, and individuals who are sick or with a weakened immune system. The children of Haskell Institute can be accounted for in all these categories, attributed from poor diet, little to no healthcare, stress, and intense labor.

Image: Haskell Institute Hospital. Douglas County Historical Society archives.

Death Documentation is Unreliable

We must remember that not every death was documented. Many of the children’s deaths either went unreported, marked as runaways, or labeled as something completely different. According to researchers Jeanne Klein and Charles Haines, authors from Embattled Lawrence, Volume 2, the number of deaths at Haskell Institute was anywhere from 250-1,200 students.

The total number of reported deaths is nowhere near what it actually, and truthfully is; and we may never know.

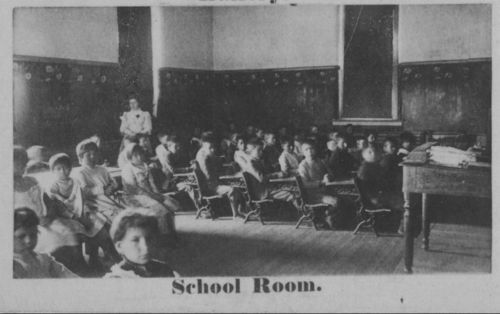

Haskell Institute classroom 1884-1909. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

Much-Needed Stimuli

Haskell, similar to other boarding schools, developed a plethora of clubs and activities for the students. These extracurricular activities not only provided a much-needed outlet for the students, whose ages ranged from three to thirty, but also worked within the process of assimilation. By exposing non-stimulated students and providing socialization and physical stimuli, students could quickly associate the fun within these activities with being American.

Above is an image of Haskell Institute students in the school’s garden 1900-1920. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

Extracurricular Activities

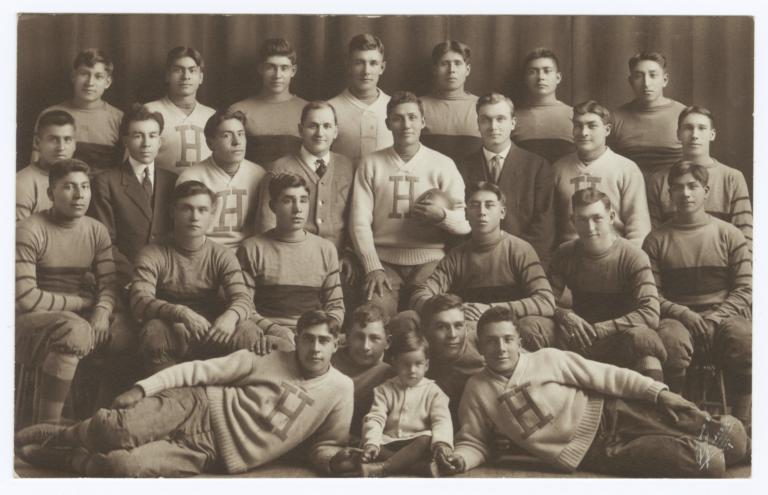

Like most schools, athletics became a staple in Boarding Schools, Haskell Institute especially. Clubs like baseball, football, YMCA/YWCA, and basketball became popular among students and non-students alike. This gave opportunities to the students like competing in the Olympics or being recruited to play for various respected universities.

Football Club

Haskell Institute played many universities and high schools both in and out of Kansas. The wide range of opponents was due to the wide age range within Boarding Schools. Children and adults both attending presented more opportunities for the school itself and would give the school a good name. In football, Haskell Institute played many universities such as Baylor, Texas A&M, Chilocco, Nebraska, and others.

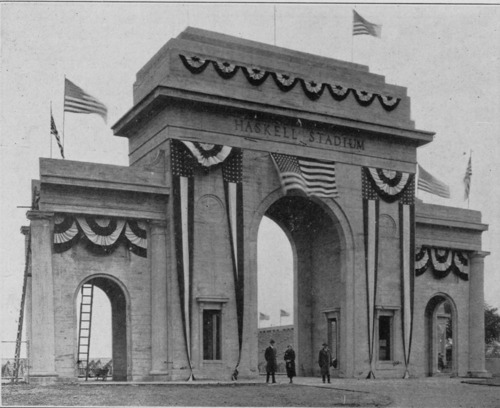

Arch of Memoriam

In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was passed, granting Indigenous people the status of American Citizens. This was a great achievement for Indigenous peoples, yet felt confusing. Are we not citizens in our own land? In 1926, a memorial arch was built, honoring students who served in World War One, and to show Haskell’s assimilation progression.

This arch was made possible by donations from members of the Quapaw and Osage Nations.

The impressive Haskell stadium arch. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

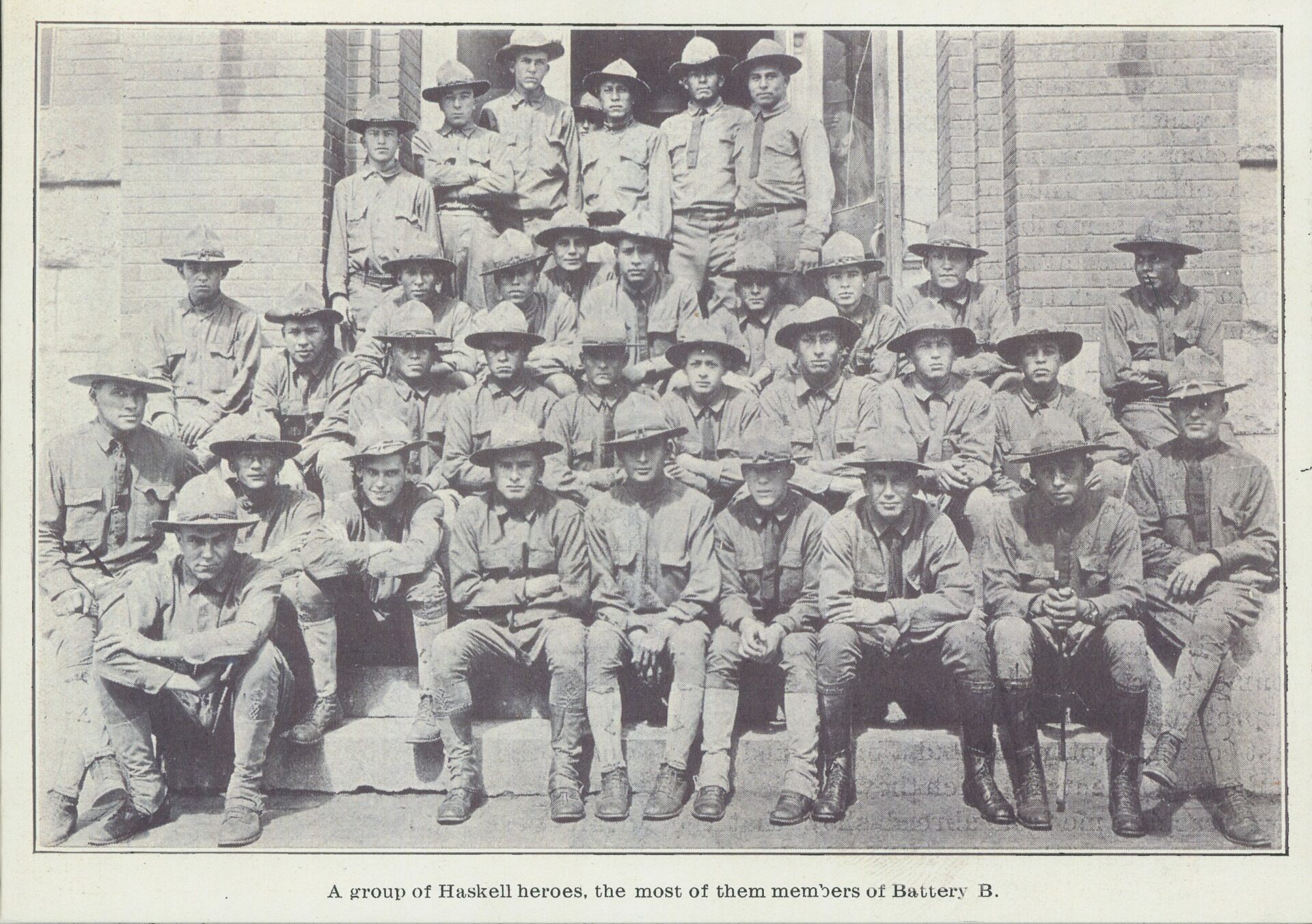

Haskell War Heroes

The argument of whether Indigenous peoples were civilized enough to be considered Americans became an issue, despite student’s enrollment in Boarding Schools and their careers after. But the counterargument of Indigenous people’s participation in World War I proved to doubters that Indigenous people were becoming truly “civilized” members of society.

Imaged below is a beaded bag from the Kiowa Tribe decorated with patriotic emblems, alongside the Haskell Heroes who participated in World War 1. Left: Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Right: Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

1926 Intertribal

Following the Haskell v. Bucknell football game, which Haskell Institute won 36-0, was a three-day intertribal powwow celebration from October 27-30. This powwow displayed various dancing contests, a Buffalo barbeque, a beautiful baby contest, and a chance to show the advancement of Indigenous students who had or were currently attending Haskell. Hundreds of tribes traveled to Haskell Institute and created a campsite on Haskell grounds for the weekend event. Whites ridiculed them for being tainted with savagism.

Imaged below, various powwow dancers dressed in their regalia. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

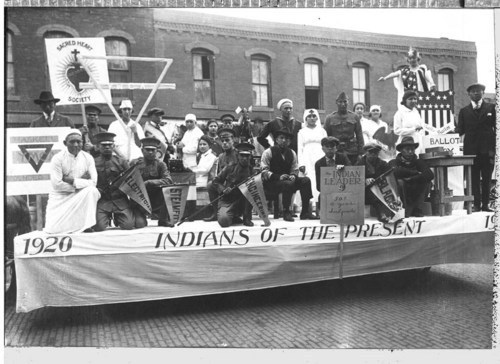

1926 Parade

Another way for Haskell Institute to show their advancement in assimilation was in their parade down Massachusetts Street, on floats depicting an “Indians of the Past 1620-1492” banner, where Haskell Institute students were dressed as pilgrims, Christian priest, and Indians in their regalia. Alongside was an “Indians of the Present 1920-“ float and banner, depicting military men, nurses and voters. These two floats showed their progression as American Indians.

Depicted above are the Haskell Institute students of 1926 participating in the schools’ parade. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

Haskell Institute Band

The institute band became a popular extracurricular. Haskell Institute students would participate in marching band from the 1900’s-2015. The Haskell band would perform at the World Fair in 1904 in St. Louis and the band would come out and play for the city of Lawrence for major town events.

Although Haskell Institute was morphing into what seemed to mimic a regular grade school and high school, it still was an Indian Training School by reinforcing the ideas of Normal America unto Indigenous children.

Haskell Institue band in a group photo. Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply.

“The Star-Spangled Banner,” played by the Edison Military Band, ca. 1902. This was one of the songs performed by the Haskell Institute Band. Courtesy of the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Society.

The Meriam Report

An 800-page research report on the living conditions of Indigenous people was created by Lewis Meriam and his team of researchers in 1928. The Problem of Indian Administration, or The Meriam Report, would point out the heinous conditions of Indian life and the spread and mistreatment of illnesses like Trachoma, Tuberculosis, and Malnourishment. The Meriam Report also talked about how these conditions could be improved, which would be greatly ignored.

The team of researchers who visited Haskell found that the staff put more effort into their athletics rather than putting in effort into their academics, which would create issues for non-athletic students.

This affected thousands of Indigenous people and students by exposing the horrible realities that they endured for years and would shed light on how Indigenous people were actually living, contrary to spoon-fed lies.

Lewis Meriam imaged above.

The Generations of Today

Haskell has been transformed and molded into numerous tools of education for the Indian child. Named Haskell Institute in 1887 and remained giving a strict Boarding School education until 1927, when high school classes began being offered to Haskell students, this soon transformed into a vocational technical institution to give students opportunities after completing high school, and in 1965 the last high school class of Haskell Institute graduated. Throughout the years of Haskell history, Indigenous staff would be introduced to the school, possibly creating familiarity for the students. In 1970 Haskell became Haskell Indian Junior College, and in 1992 it finally transitioned into Haskell Indian Nations University, the University that thousands of Indigenous people have attended and graduated from.

From a history of despair and colonization, Haskell Indian Nations University has flourished into opportunity, connection, and community for hundreds of Indigenous students. From the hardships of the children of Haskell Institute, the students of Haskell Indian Nations University are able to bloom with knowledge and pride today.

Imaged above is a side-by-side of previous Haskell Institute students (1887-1909) and my classmates from Haskell Indian Nations University (2024). Left: Kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society. Copy and reuse restrictions apply. Right: Courtesy of Kennedy Murphy.

Thank you/Ah-ho.

My name is Kennedy Murphy, and I am a senior at Haskell Indian Nations University and will be getting my bachelors in Indigenous and American Indian Studies in the Spring of 2024. I am a member of the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma and the Kiowa Tribe. I come from Carnegie Oklahoma where my biggest supporter is my mother, Jarrnetta Taylor.

I will be the first in my family to graduate from college and the first to attend graduate school. I plan on keeping my ancestor’s history alive and truthful, our history deserves proper recognition and respect. I love learning Indigenous history, I enjoy reading, and doing freelance research on various Indigenous topics such as genetics, gender, entertainment, disease, art, and jewelry.

Recommended Books

Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928 David Wallace Adams 1995– Adams speaks about the realities of Boarding Schools and how children within the schools actually lived, their process of adaptation, and the influences of American culture and how this impacted the students.

Boarding School Seasons Brenda J. Child 2012– Child relays the history of the two boarding schools Flandreau Boarding School in Flandreau SD, and Haskell Institute here in Lawrence, Kansas, through personal letters from, students, parents, and staff. These letters show the reader the realities of the broken English and the broken hearts of those impacted by boarding schools.

Embattled Lawrence Volume 2: The Enduring Struggle for Freedom Watkins Museum of History 2023– This book goes into great detail surrounding the history of Lawrence, Kansas, touching on Haskell’s history and transformation.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants Robin Wall Kimmerer 2013– Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass gives excellent credit to the Indigenous communities and their Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Indigenous science, which has been greatly dismissed and ridiculed. Kimmerer is able to share her wisdom as an Indigenous woman in science, the traditional teachings of her ancestors, and the teachings of our Mother Earth.

Voices from Haskell: Indian Students between Two Worlds, 1884-1928 Myriam Vuckovic 2008- Concentrating on the school’s early years, the author describes how administrators and government officials forced Indian students into an assimilation program that sought to rob them of their Native cultures, yet ironically encouraged students to build Indian identity with students from other tribes and places.